The treasure lore of Hart Island

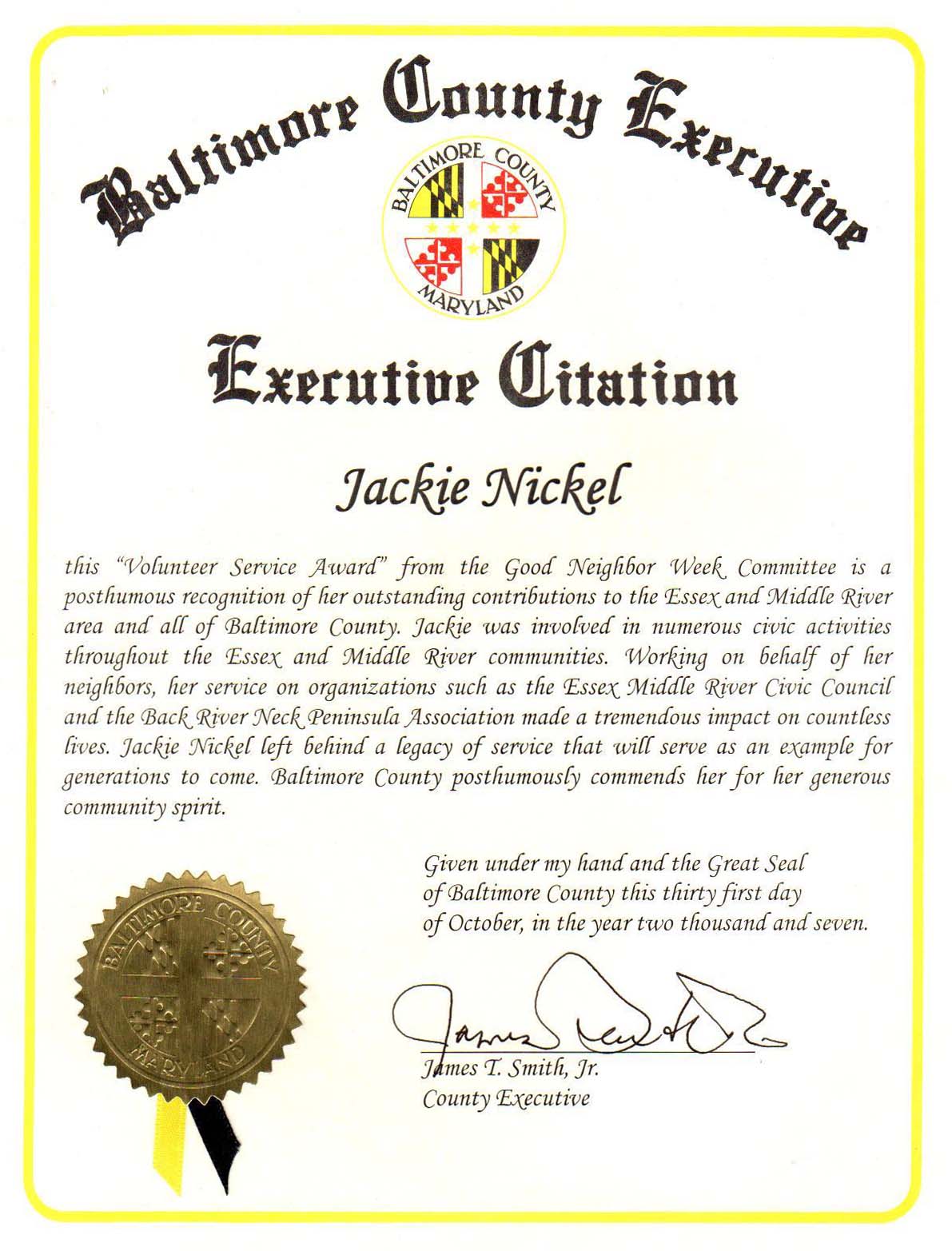

By Jackie Nickel

A friend recently shared with me a tale worth repeating and preserving. This legend, centering on Hart Island (now part of a dredged spoils disposal site) was first told in both daily newspapers, The Baltimore News American and The Evening Sun, in 1913. It was revived in 1971 in a dissertation written by Darryl C. Ruppert, “The Treasure Trove of Hart’s Island,” and shared with the Heritage Society of Essex and Middle River, which was given permission to reproduce it. That is how my friend acquired a copy, which she passed on to me.

Joseph Hart, a wealthy Englishman born of a prominent family, lived on Hart Island in the mid-1800s and it was there, it is said, he buried his fortune. The man, a tavern and livery owner, was described as an eccentric who feared robbers and thus buried his fortune. He died in 1852, leaving a wife and several daughters. The secret of exactly where his treasure was buried seemingly died with him.

The story of Hart’s buried gold was resurrected in 1913 when six men, led by a John Wagner, made an effort to access the island to search for what was described as a treasure trove of buried treasure. The team had assembled information, from unidentified sources, describing Joseph as a miser who hid his gold beneath the ground because he was afraid to keep it in the house and didn’t trust banking institutions. They claimed they had a map indicating treasure buried near a waterfall, the gold contained in two boxes and two tanks, no more than three feet deep. The value, in both bars and coin, was estimated at $15,000, a large sum for the day.

When the treasure seekers went public with their mission, the new owner (the property had passed through several hands) denied them entry onto the island. In newspaper accounts, where two of Hart’s daughters were interviewed, their long held secret of buried gold was revealed. And the survivors immediately laid claim to any treasure that might be found.

Anyone who knew Hart Island was familiar with the flat, marshy terrain with no possibility of a waterfall. Wagner, however, determined waterfall to mean a gully or “a falling away of ground to cause drainage of water.” On the north side of the island were some long neglected irrigation canals that he considered as fitting the description of the treasure’s location.

In news accounts, one of the daughters of Joseph Hart reported seeing her father unearthing a keg of gold coins and moving it to another location. Joseph had been robbed more than once and feared burglars, she said. Only his wife knew where Hart buried his gold for safekeeping. And she went to her grave without revealing the location to her daughters.

The Harts had acquired the island in 1821. At the time it consisted of 264 acres, while Millers Island, which they also owned, was 124 acres. There was a large “rough hewn timber house with walnut window frames” built on the island before the Harts owned it. “Luxuriant trumpet vines” covered one side of the house, which was leased to hunters during ducking season. A grove of sweet gum trees was nearby. The family evidently lived in Baltimore City near Hart’s Tavern on Front St. and spent summer months on the island.

Mr. Hart died in 1852, leaving the children to search relentlessly for his buried gold. They finally gave up in 1858 and sold the land to Frederick Schumaker, it was reported by Mr. Ruppert. At the turn of the century the isle was the home of the Millers Island Ducking Club.

The Baltimore Atlas of 1877 shows Miller Island (or Little Island as it was labeled) to the north, with the larger Hart Island in the center, and to the south and closest to the mainland, Pleasure Island. A narrow channel separated Hart and Miller. The land eroded drastically over the decades as tides and storms took their toll. By 1933, Hart Island was down to 180 acres and Miller to 70. A bridge which had connected the islands to the mainland was destroyed by the Hurricane of 1933. It was not replaced until 1937.

Muskrat hunters took up residence at the old Hart house in 1938, trapping nine a day and receiving at least 70¢ for each pelt sold to furriers. By 1943, the 100-year-old clubhouse had collapsed and its foundation was washing away. In 1947, Baltimore political figure George P. Mahoney purchased the property with plans for building new homes and recreational areas. His project never got off the ground, although New Bay Shore Park was established.

By the late 40s, Hart had eroded more and by 1959 it had shrunk to 150 acres while Miller was just 52. Mahoney sold the isles to Bethlehem Steel in 1965.

Only one treasure seeker was reported to have found any gold on the beach of Hart Island over the years: One gold coin, possibly English.

When Ruppert penned the tale of buried treasure over 30 years ago, the threat of Hart and Miller Islands being converted into a dike to hold dredged spoils was looming. Beth Steel had sold the land to the Langenfelder sand and gravel company, which was negotiating with the state government. He surmised any trove buried near the mid-1800s shoreline was already under water. Today it would be under tens of thousands of tons of material dredged from harbor channels and bay tributaries.

Sue Creek’s famous Pottery Farm