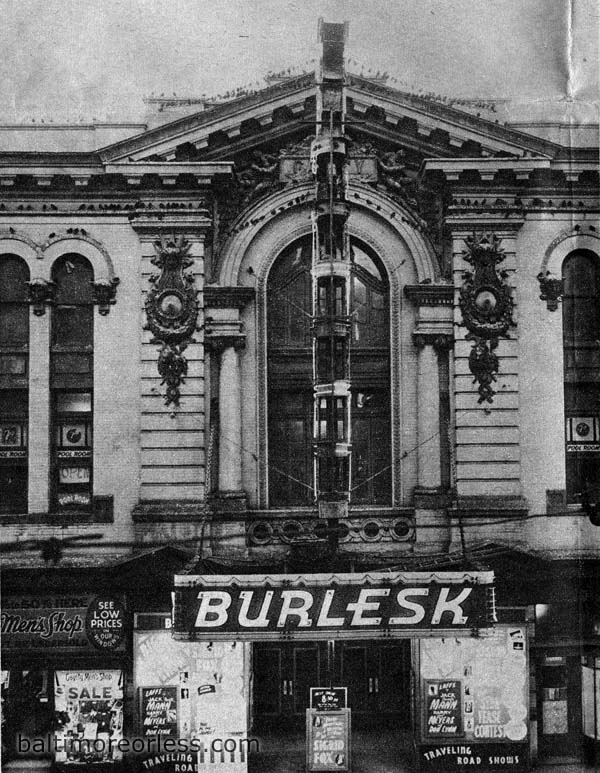

Gayety Theater at Baltimore and Frederick Streets, as it appeared in its heyday. Perennial birds, which sometimes short-circuited marquee, can be seen on roof.

I Remember… Burlesque and the Girl on the Sign at the Gayety Theater

By John H. Nickel, The Sun Magazine, 5/31/1970

I don’t have much heart to go down to The Block anymore. The flavor of it has been gone for me since the Gayety Theater burned on the first day of Christmas week.

I drop by now and then to see my friends. But the spirit of that whole section seemed to die when the kicking girl — our animated neon sign which was almost four stories high — quit kicking.

The baggy pants comedians and the pretty girls still put on a sort of the old Gayety type burlesque in a smaller theater nearby, but there isn’t much stage room there for them to really give out, and the stripteasers are taking it all off to phonograph music, with a drummer sitting in to accentuate the bumps and grinds.

For 60 years the Gayety brought to Baltimore this country’s finest burlesque talents — strippers like Ann Corio, Margie Hart, Hinda Wassau, Blaze Starr, Valerie Parks, the Carroll Sisters, and such funny men as Phil Silvers, Jackie Gleason, Joe Penner, Rags Ragland, Red Skelton, Billy Hagen, Hap Hyatt, Billy Boob Reed. It was known all over the world, its fame spread throughout World War II by practically every soldier, sailor and Marine who ever did a week on the town in Baltimore.

United States senators, diplomats, admirals and generals have sat among the Gayety’s patrons. Easily 30 percent of the clientele were women.

My father, John Nickel, made the Gayety what it was.

He had come to Baltimore around 1898 when his mother brought her family of four sons and a daughter over from Germany. My father had been christened Johann, and although he changed his name to John on this side, his friends called him “Hon” all his life.

His mother bought several acres on Colgate Creek, near the site of the old Riverview Park, and for some time operated a dairy farm. But my father, despite his lack of education, had another life in mind for himself. He was a terrific promoter, and as a young man somehow came into possession of the Natpins, a small hotel (later to become the Commercial) at Baltimore and Frederick Streets.

This was an inexpensive place much patronized by traveling theatrical troupes, and here my father learned that he loved show people. He had the reputation of never turning away down and outers, and his attitude won him many lifelong friends among performers.

In 1910 what was to become the Gayety was broke, in the hands of the receivers. My father bought it with not much more than a handshake. He had practically no money, but he had the infectious ability to promote. I strongly suspect that one thing which helped him operate in the early years, when money was so scarce, was the loyalty of his show people friends.

I was born in 1918, and was running errands and making myself useful around the theater when I was a grade schooler. Show people there gave me the name of “Bud .” When I finished school at Calvert Hall, I went right to work, selling tickets. Before long I began helping my father book the acts, and I learned the business that way.

We had the best burlesque in the country. We booked mostly through the Hirst Circuit, out of New York. The Wheel, as show people called it, took in Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk, Pittsburgh , Boston, Youngstown, Scranton, Allentown, Cleveland, mostly one-week runs, with one and two-night stands at smaller towns along the route.

A thousand people filled the Gayety — orchestra seats, balcony and boxes — and we sold out quite often. When Ann Corio came to town we turned away customers. She was a big enough draw that she could demand her own terms, which often amounted to $1,200 plus a house percentage which boosted her to $2,000 a week — big money now, and much bigger in the 1930’s and 1940’s.

A show ran about 2 ½ hours. There was a star stripper, a No. 2 and often a No. 3 stripper, and three minor take-it-off performers. There’d be a big name comedy team, possibly one or two other comics working alone. There was a house singer, who did two numbers each show, usually as accompaniment for a costume number staged by the traveling chorus of 12 showgirls.

Practically every rainy day and clear night meant good business. On rainy days the theater would be packed with customers whose work was hampered by bad weather, mostly salesmen. There was continuous entertainment from noon to 5 P.M., 8.30 to 11 P.M. The place was open seven days a week, and it closed only during the hot spell from late May to early September, for it had no air conditioning.

The Gayety nightclub opened shortly after the theater, and it ran until Repeal on soft drinks and near beer. At the end of Prohibition it became a great deal more profitable business, much of it from theater patrons. We had a ladies’ wash room in the theater, but the men’ s room was downstairs in the night club. Most of the gentlemen who went down there stayed over for the floor show, more burlesque entertainment.

After my father died in 1950, I ran both the theater and the club for a while with my sister, Mrs. Marian Nickel McKew. Later we leased out the theater and spent our full time managing the club.

But the big old burlesque house was our first love. What a pain in the neck the big animated neon kicking girl sign was. Pigeons and starlings picked it as a roosting spot because they liked the warmth of all the lights. The mess they created was forever short-circuiting the wiring in the sign. But, because it was a landmark known around the world, we never thought of replacing it.

Like many other Baltimoreans, I miss the kicking girl. I don’t think The Block will ever be the same without her.